I’m a little behind on this. Canzonas Americanas with music by Derek Bermel, was released last November, and since then it’s received decent reviews. The Guardian says Alarm Will Sound plays with “panache,“and Anne Midgette of the Washington Post placed the album in her best of 2012. (And the consumers on Amazon and iTunes seem to like it as well.)

The recording contains all music of Derek Bermel, including the title work Cazonas Americanas which was written for the LA Phil in 2010, Three Rivers (2001), Continental Divide (1996) and Hot Zone (1995). In addition to AWS, the album features vocal performances by Luciana Souza (Grammy award winner) on Canzonas, Kiera Duffy on At the End of the World (2000) and Timothy Jones on Natural Selection (2000).

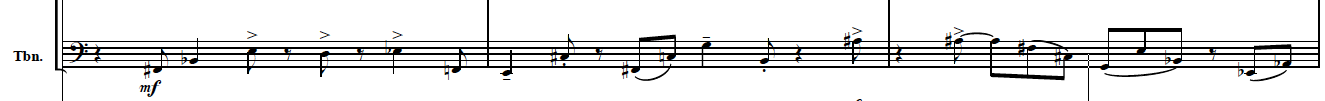

I like that the trombone actually gets some work in Derek’s music. In Three Rivers the trombone is part of the funky, lugubrious, dissonant line that occurs throughout the piece.

The part is entirely playable on tenor trombone with the exception of one low B that happens towards the beginning but has a feel that is very well suited to the bass trombone.

The trombone also participates in the smoother, quicker cascading passages (one example is at 1:30, the trombone has a more prominent role in the subsequent entrances) that recur.

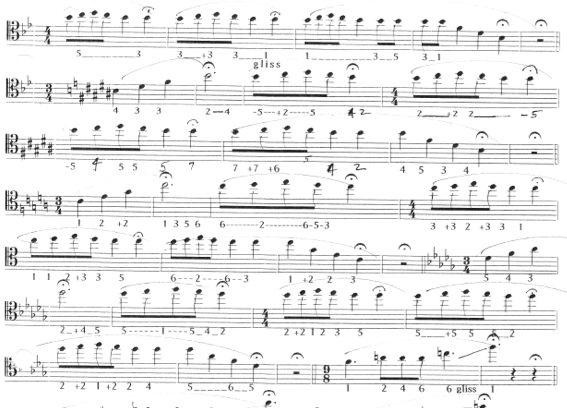

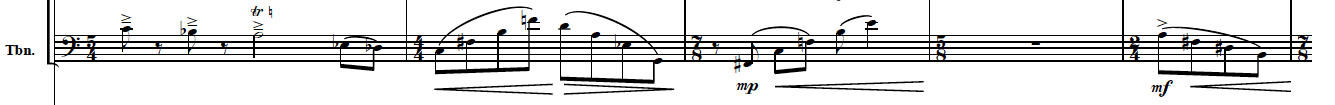

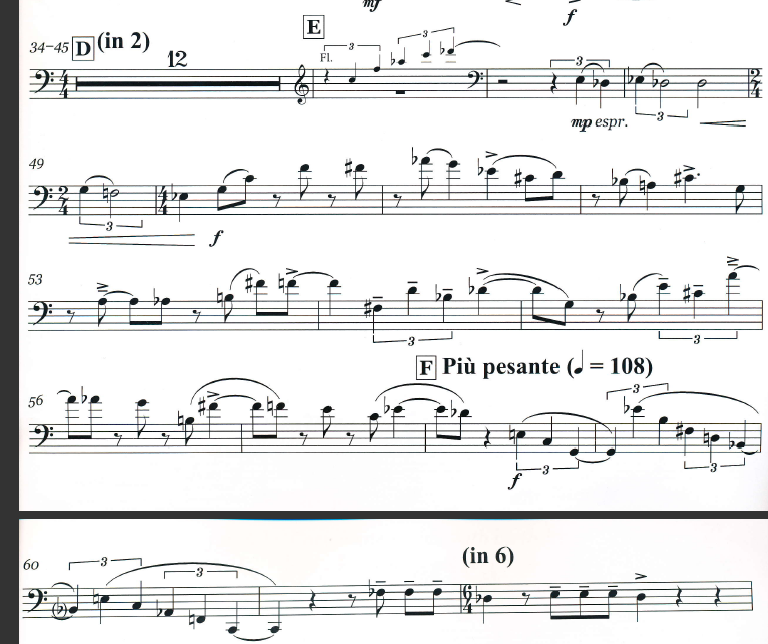

There are also good times to be had for the trombone in Canzonas Americanas. Check the first movement for things like this:

This passage is part of a pretty densely scored section. I found I had to play fairly loudly to be heard (c. 1:40):

And the third movement has a nice passage where the brass joins the fantastic electric guitar/bass part:

The rest of the disc is just as interesting. Natural Selection is written in a way that makes the ensemble sound bigger than it is. The trombone range is wide: in the third song “Got My Bag of Brown Shoes” it goes down to pedal F and as high as E at the top of the treble clef (with some other “as high as possible” pitches). The first song, “One Fly,” reminded me of the fly episode of Breaking Bad, so I give you the Bermel/Breaking Bad mashup.

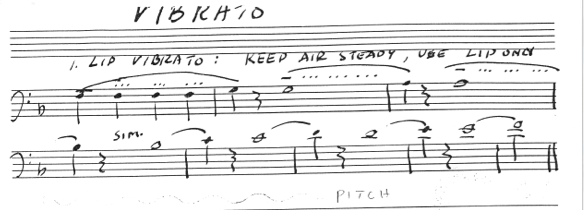

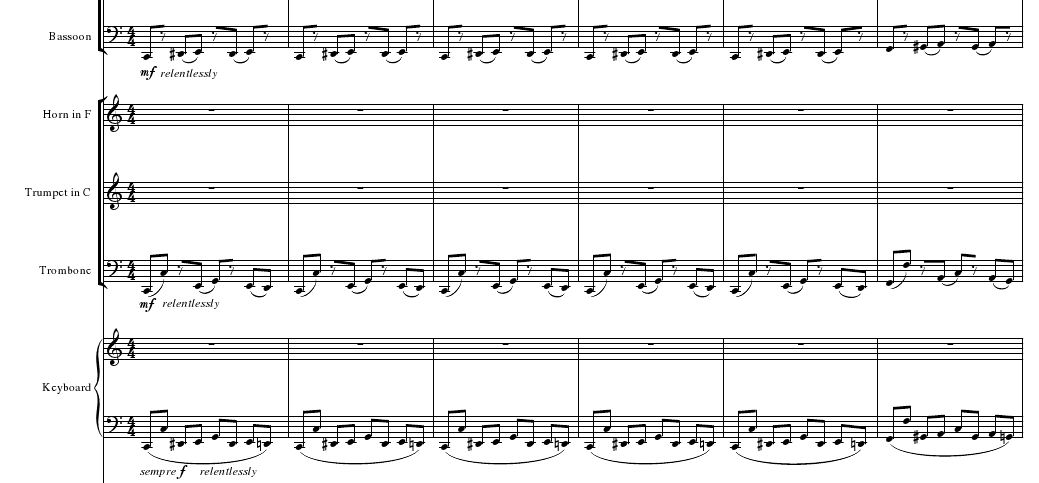

Bonus: Derek also arranged some Conlon Nancarrow for Alarm Will Sound that we recorded for our album a/rhythmia. Lots of trombone work to be done in this one too. The opening looks like a no brainer for the bass trombone. The trombone should hocket with the bassoon to form the boogie woogie piano part. If you have short arms like me you can end up doing damage to yourself trying to play all those low C’s on a tenor trombone.

But just a short while later in the transcription the trombone part has a duet with the trumpet that takes it up to E flat at the top of the treble clef, a decidedly un-bass trombone lick.

The challenges make it fun. Do your best to enjoy it if you ever have the chance to work it up.