No. 42 (In the Alps), Richard Ayres

Melodrama for soprano and chamber orchestra (2008)

No. 42 (In The Alps) by Richard Ayres is an orchestral trombonist’s dream: part Strauss, part Rossini, part Mahler, mostly hilarious. Here’s how the composer Richard Ayres describes it:

No.42 (In the Alps) could perhaps best be described as a melodrama. It combines many of the subjects that fascinate me: the relationship of text narrative and musical narrative, the history of opera, early cinema, the theatrical practices of the nineteenth century, along with the folk and popular music of the Alpine region.

A girl (the soprano), stranded on top of an un-climbable mountain peak as a young baby, is taught to sing by the mountain animals. Young Bobli lives in the village far below the un-climbable peak. He was born mute and communicates with the world by playing the trumpet. Bobli hears the soprano’s song drifting down into the valley. The soprano listens to Bobli’s trumpet tunes blown up to her by the wind. They are both enchanted.

The three acts are separated by interludes describing how three animals experience time passing in relation to a musical tempo.

Like any self respecting melodrama the text and music combine to depict or imply a wide ranging theatrical adventure, in this piece starting at the Creation (or the big bang), a lonely existence, scenes of rustic village life, some carpentry, many mountain goats, unrequited love, and ending in a quest destined to fail. In a live performance the text [provided with the performance material] is to be projected on a screen behind the musicians in the style of silent movie intertitles.

Richard Ayres

In the Alps calls for a brass section with two trumpets, two French horns, bass trombone, and tuba. The bass trombone (and this is definitely a bass trombone part) performs both as an ensemble voice as well as a soloist. The piece was written for the Netherlands Blazers Ensemble with Barbara Hannigan (recording available here), and the bass trombone part created with Brandt Attema‘s playing in mind.

Act I, Prelude – Straussian

The trombone first enters as an ensemble member at Rehearsal D (Act I, Prelude). This loud moment comes as a surprise after an opening reminiscent of the beginning of Mahler’s First Symphony (ppp). The trombone is doubled with the tuba and both are marked only f, whereas the low woodwinds and double bass, playing different material, are marked fff. This is likely a case of the composer being aware that a trombone f is different than a bassoon f and attempting to balance the instruments.

Between rhl D and E the brass section plays a Straussian klangfarbenmelodie. At rhl E the ensemble is quiet again and tension builds leading to rhl F. Rhl F contains none of the lyricism of D. The ensemble is in almost complete rhythmic unison on these ff notes. The motives shift abruptly and at unexpected times due to the meter changes.

Rhl G is a sweep of contrary motion that gathers momentum and leads us to full-ensemble rhythmic unison beginning three measures before rhl H.

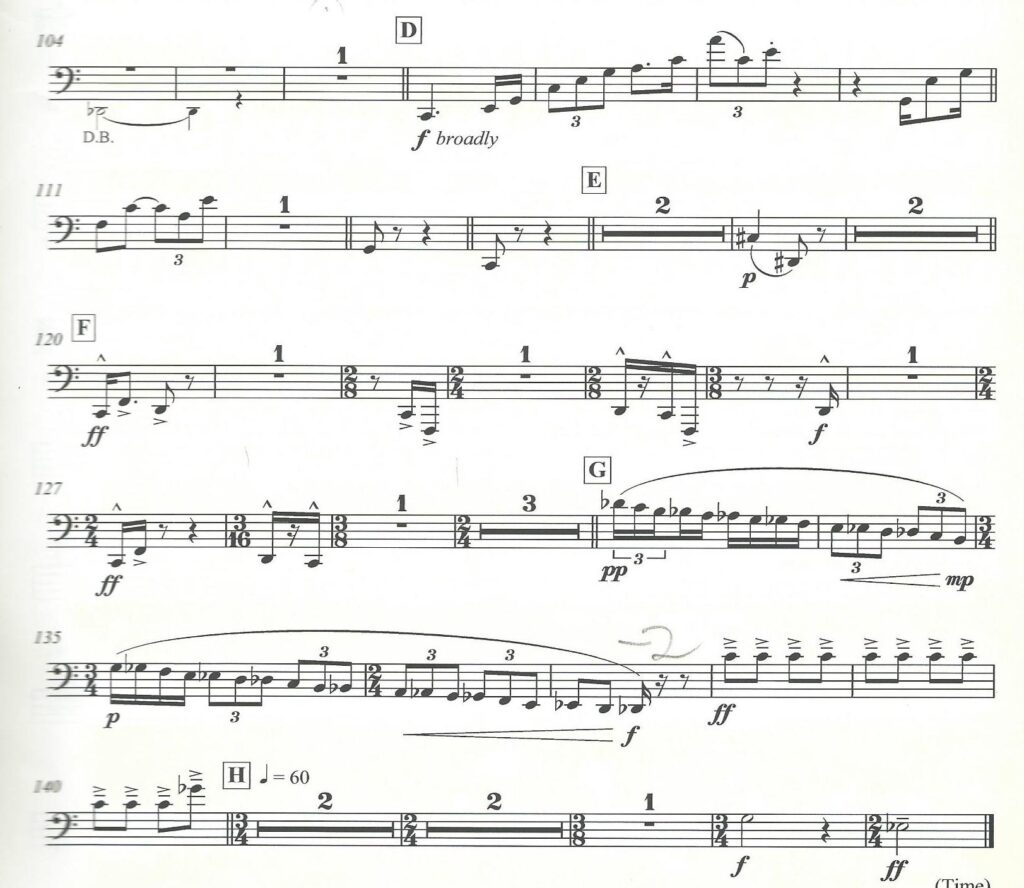

Act I, Scene 1 – Snoring Bears

The next trombone entrance is with tuba, contrabassoon, and double bass at the end of Act I, Scene 1. The scene introduces the animals of the Alps one-by-one starting with the song of the nightingale, then the “song” of the cicada, then the hooting of the owl, then the toad, and on and on until the snoring of the mountain bear. By the time the low quartet enters the orchestration is quite thick and it might take a bit of effort to from the full ensemble and quartet to create a balance where the snoring can be heard.

(Note: I’m skipping some fun passages but I feel the need to be a bit choosy about things to include.)

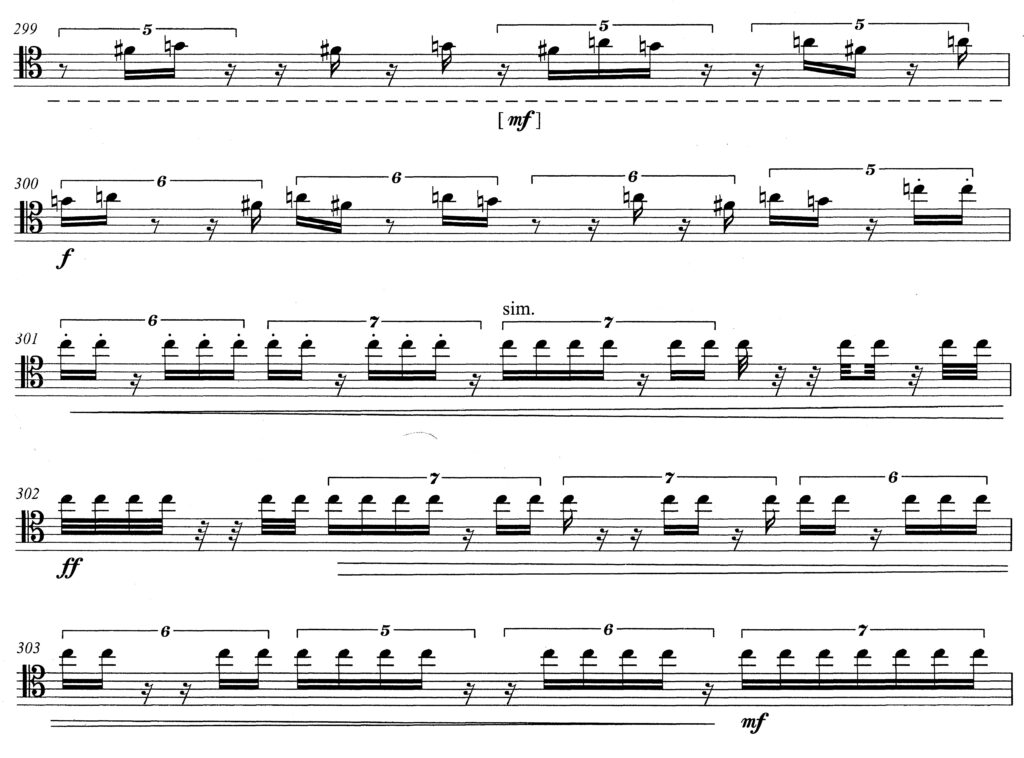

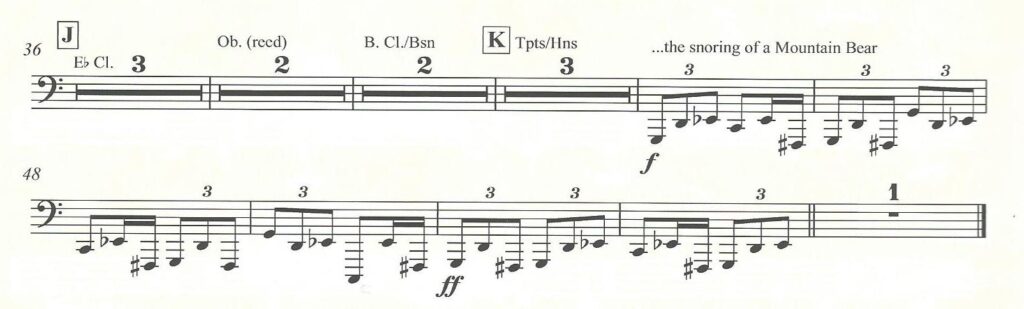

Act II, Scene 4 – “Bobli Dance”

“Bobli’s Dance” (Act II, Scene 4) is a riotous, warped polka that switches between simple and compound subdivisions. While the trombone has the melody at rhl L, it’s secondary to the trumpet (Bobli) who plays “rough, indistinct pedal tones” only occasionally. Bobli is learning to play the trumpet and the rest of the ensemble is the town band backing him up. Playing the passage accurately at tempo requires a nimble slide and special attention to articulations that switch from legato to staccato. The hairpin dynamics can be slightly tricky as well: first the subito mp at L, then the hairpin cresc/dim in the subsequent measures.

Act II, Scene 5 – Low Notes!

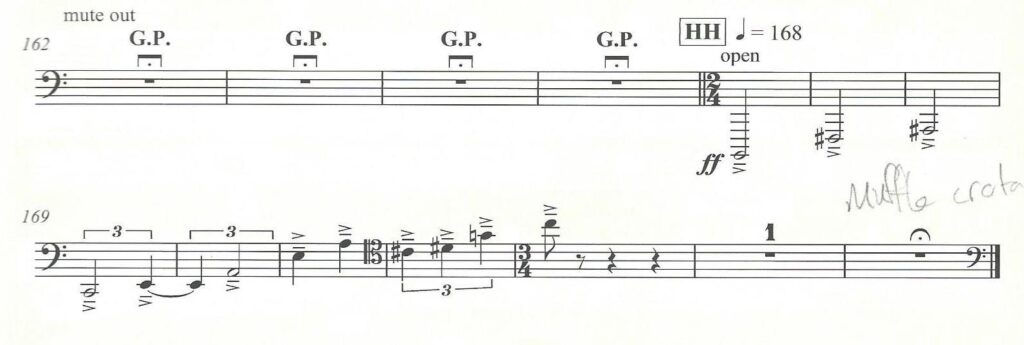

I have to point out Act II, Scene 5, rhl HH as it is the only ff pedal B I know of in the repertoire. The bass trombone is once again with our buddies contrabassoon, tuba, and double bass. The line moves, in unison, seven octaves up the ensemble ending on a ridiculously high E played as a string harmonic.

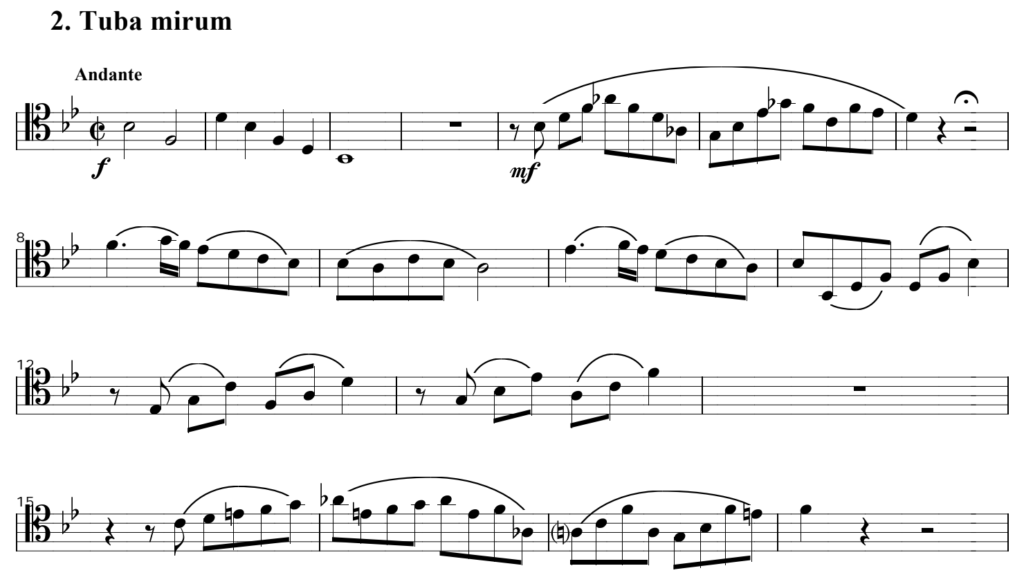

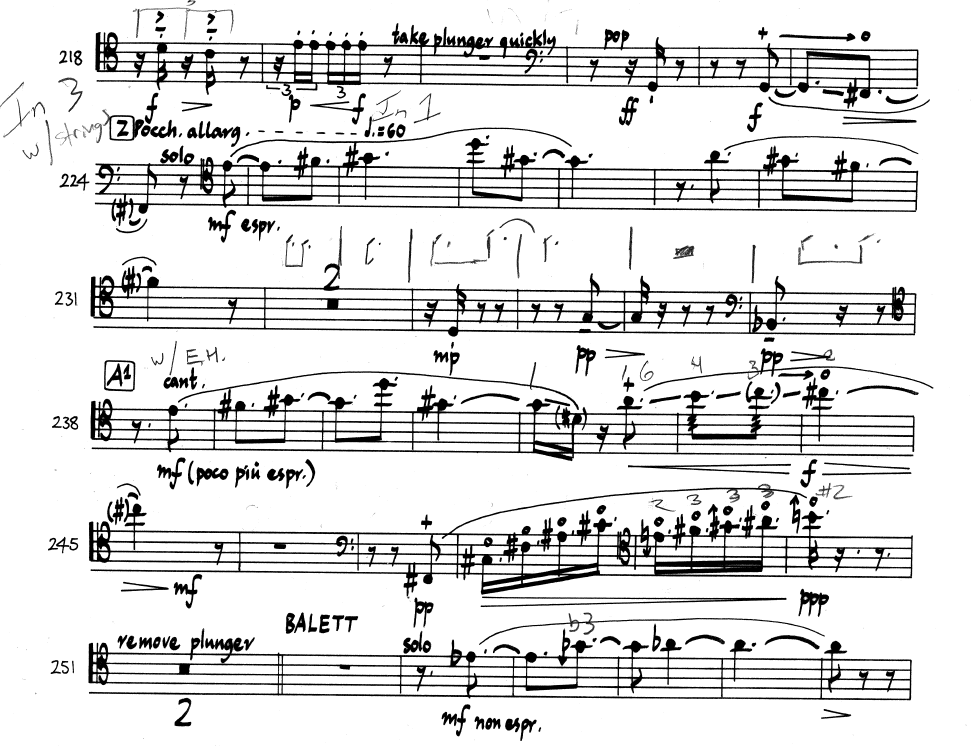

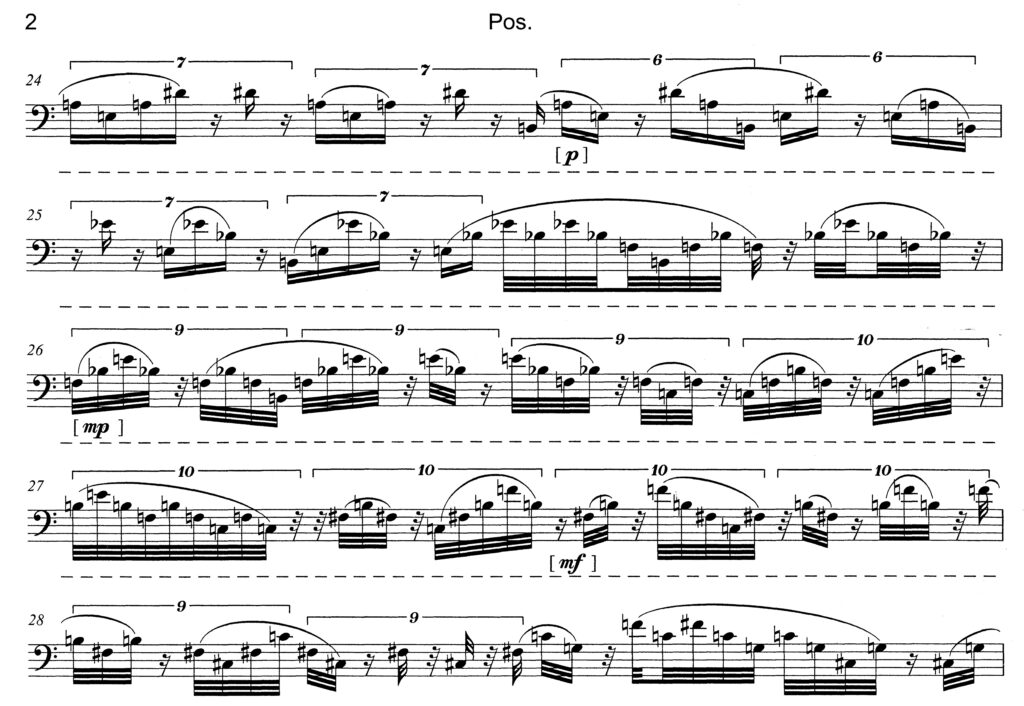

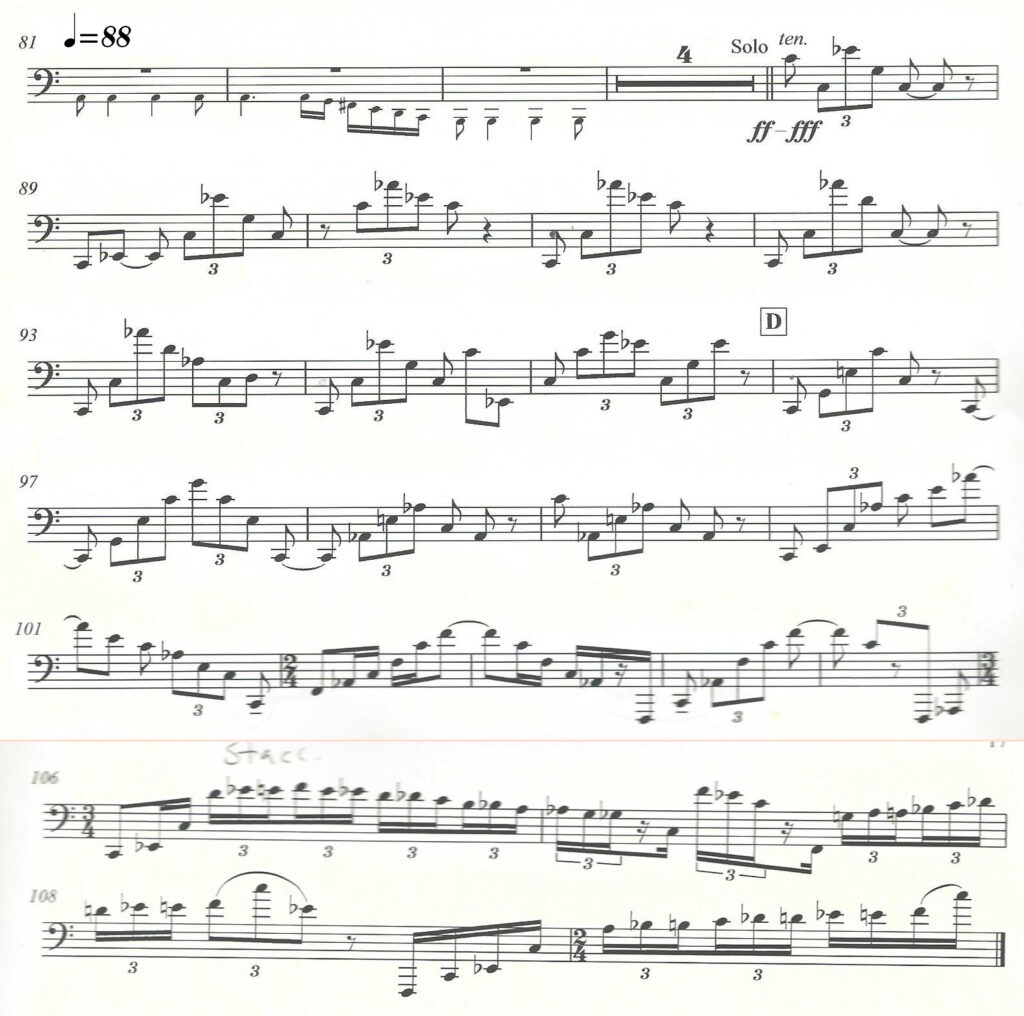

Act III, Scene 1: The Solo

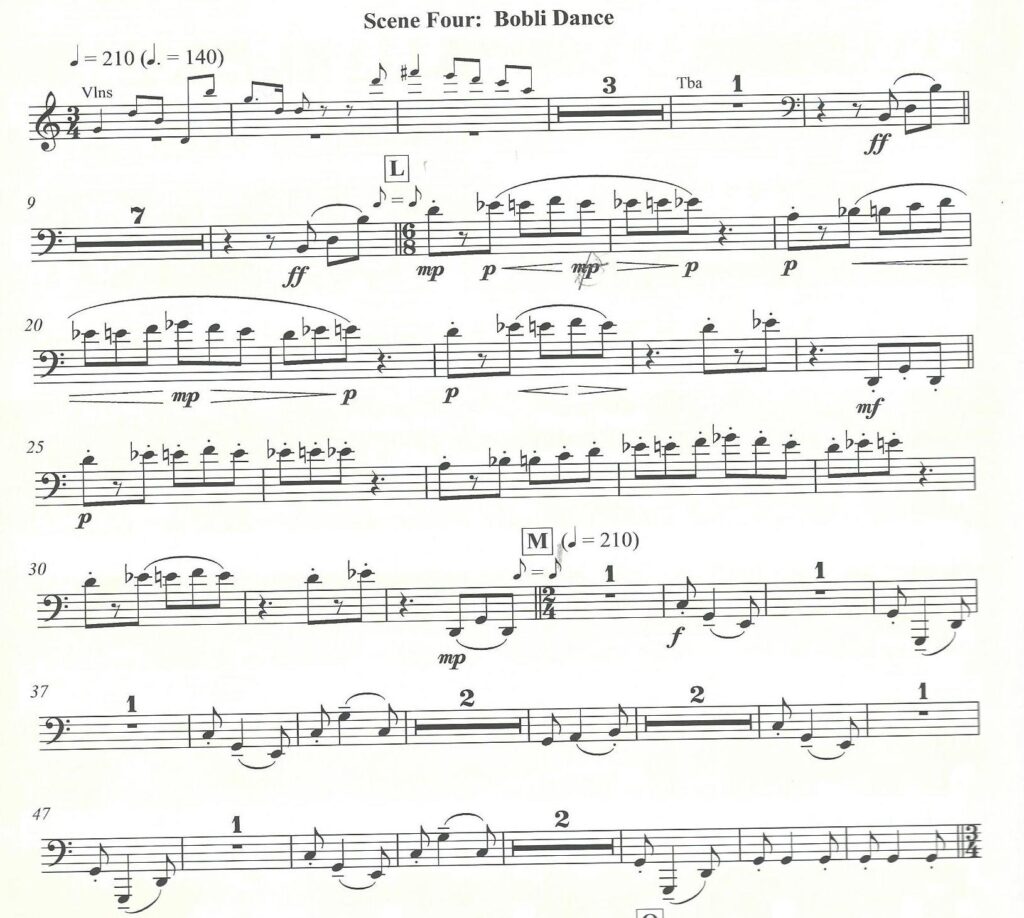

The actual “excerpt” from In the Alps happens in Act III, Scene 1, close to the end of the piece within a storm sequence.

The god Zeus is sitting atop a mountain, feeling ungod-like. He attempts some grandiosity (portrayed by a tuba solo) but when he fails he lets out a sigh that turns into a great storm. At the peak of the storm the trombone enters.

“Peak of the storm” means that once again projection can be problematic. Lone trombone against the full ensemble. What’s more, the rest of the ensemble gets to coast on less technically demanding music. Like the mountain bear earlier, it can be a challenge to project over the ensemble.

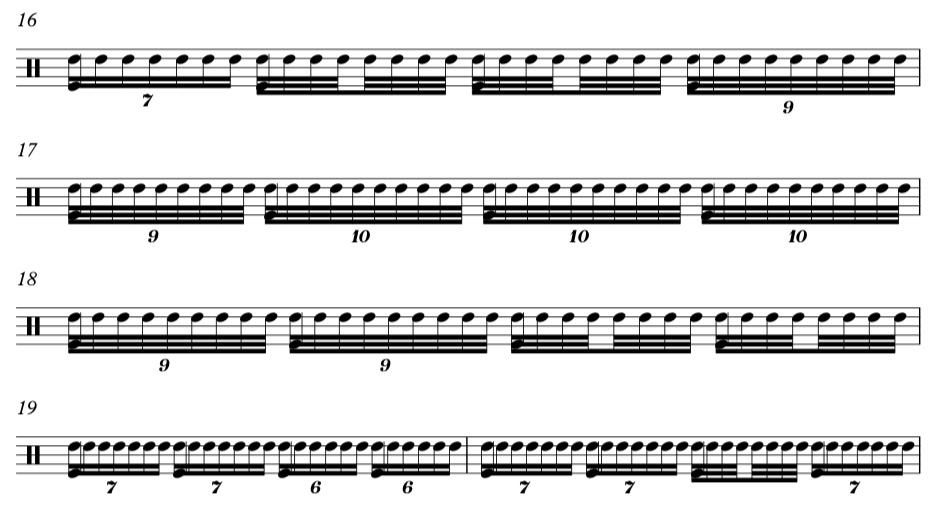

While there are significant technical demands in terms of dynamic (full, projected, evocative of a raging storm brought on by a god), range (three and a half octaves in the final phrase), and articulation (triple tonguing makes the ending easier), the rhythm provides its own challenge. The majority of measures contain triplets over beats. These can be challenging to execute. I found the two most effective methods to practice and perform the excerpt were:

1. To think in eighth note subdivisions, essentially reconceptualizing the passage as quarter notes and quarter note triplets in 6/4, and

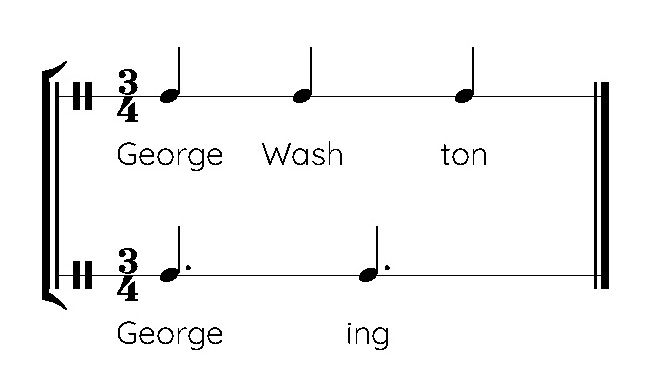

2. To internalize the feeling of where the duple falls within each hemiola, making sure that the beat lands after the second eighth note in the triplet (the “ing” of “George Wash-ing-ton”)

Bonus tip 3 that helps 100% of the time: slow it down.

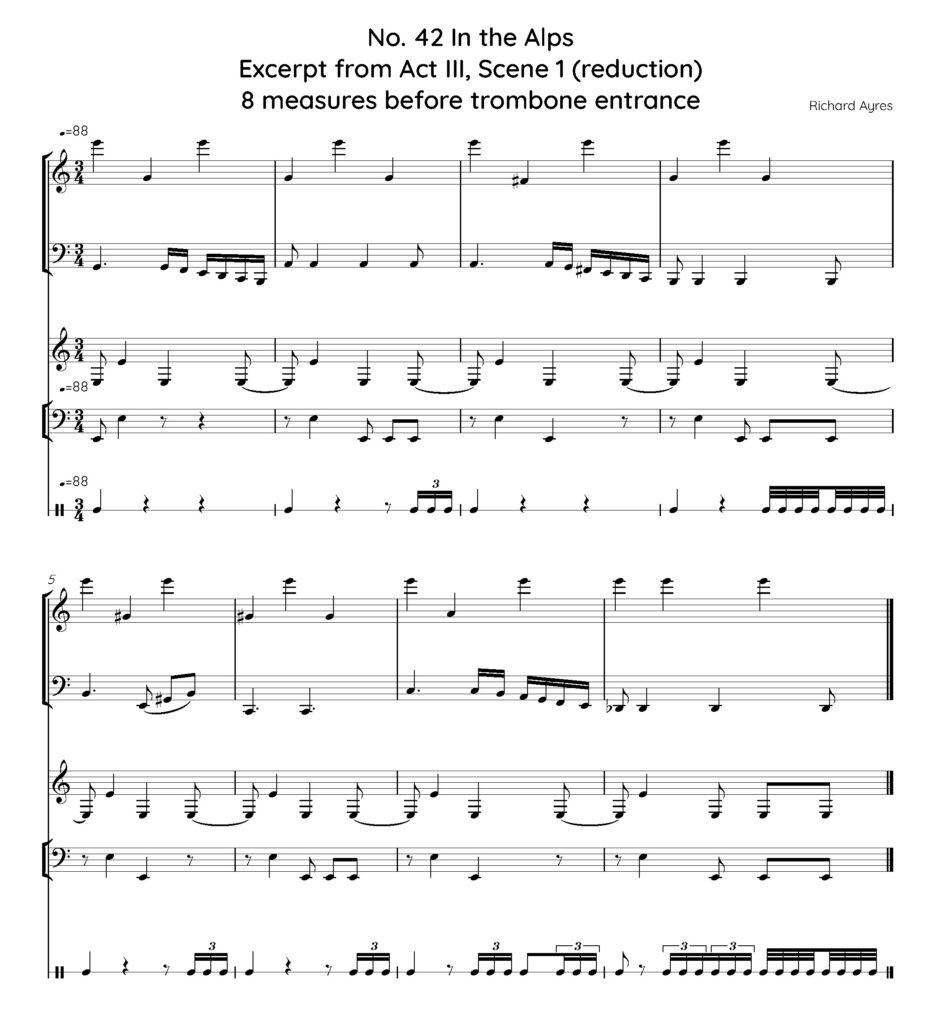

It’s also good to have an understanding of the music that occurs before the trombone entrance. In the chaos of the storm it can be easy to lose track of where you are in the measure. The horns obscure beat 1 by tying across the bar lines and the upper woodwinds and strings play quarter notes in groups of two that can create a feeling of being in 4. It’s best to cue into your buddies in the low woodwinds.

Personal story about performing this piece: This was the first piece I ever performed in concert on bass trombone. I got my instrument in July of 2013 and Alarm Will Sound performed this piece at Carnegie Hall in April of 2014. When I first saw the part I had thoughts about subbing out the gig. Instead I decided to go all in. I scheduled time every day to practice, starting in sections, under tempo, and gradually doing longer and longer chunks at faster speeds. By the time of the concert (which also included music of Donnacha Dennehy, and new works by Kate Moore and Kaki King), I was feeling alright.

Richard Ayres was there for the rehearsals and performance and had nothing to say about the solo. After the concert we all gathered at a bar in Manhattan. I joined Richard at the bar and said, “you wrote one beast of a bass trombone part.” To which he replied something to the effect of, “Oh yeah, you know you didn’t have to play all of that! When I received the commission they told me they had a monster bass trombonist in the ensemble and I should write something really hard for him. I never expected anyone else would play the part!”

Other Contemporary Trombone Excerpts:

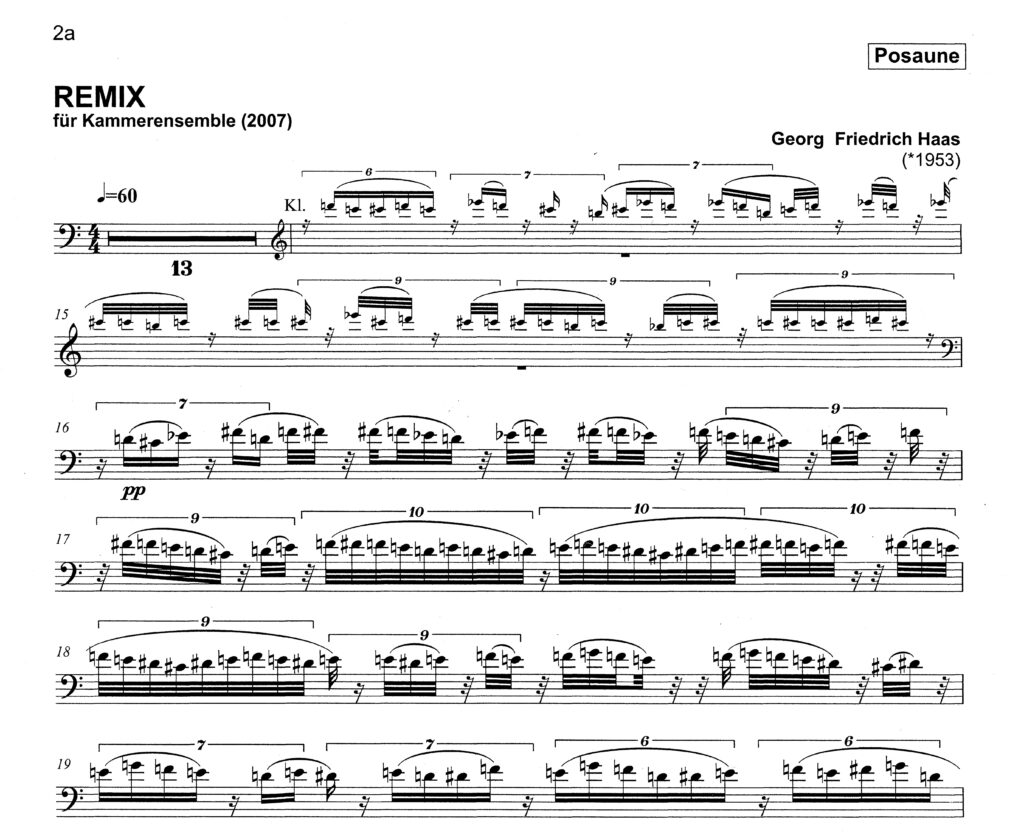

Remix by Georg Friedrich Haas