I like the sound of muted brass. Adding mutes gives brass players a broader range of colors and makes the instrument more flexible. I have, however, met plenty of trombonists who think otherwise: “I’ve worked for years perfecting my tone, how am I supposed to show it off if I stick a mute in my bell?” or “Does the composer know how softly I can play? I don’t need a mute to balance.”

But my relationship with mutes is love-hate. For as much as I love the variety of sounds I hate:

- Having to transport them.

- When they are used improperly/impossibly.

Transporting them is a pain but I can get over it. It’s a professional responsibility and besides, trombone mutes aren’t the biggest out there: I don’t envy tubists or euphonium players. But there’s a point where I have to say enough is enough or ask the composer to pay my luggage costs for the flight. Having to carry even two mutes requires me to bring an extra bag on the plane. That’s why I nearly cried when I saw this:

If you count, you’ll find seven of them. This is fine and dandy on the page but let’s look at this arsenal in reality:

You can get the perspective based on the plunger on the left. It’s your everyday run-of-the-mill clean toilet plunger. The bucket mute on the right measures in with a 6.5″ diameter and 11″ height.

So let’s assume that the composer can only express his vision by using all these mutes. Then I’m happy to carry them. Let’s look at part two of what peeves me about mutes: improper/impossible usage.

In this same piece of music I find things that look like this:

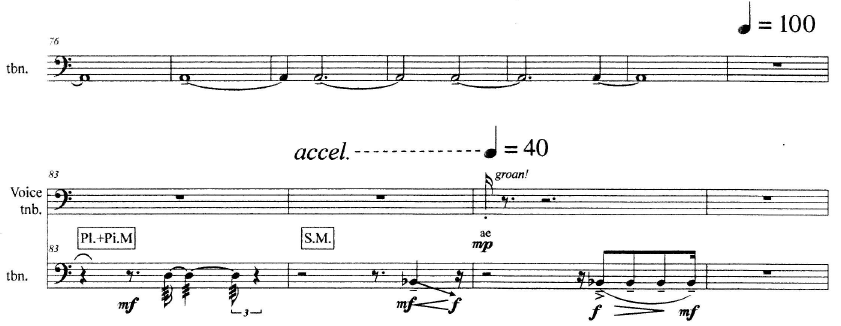

The top line of music is all ohne dämpfer. At the end of the line I have to put in a pixie mute and pick up a plunger. Five and three-quarters beats of rest at qn=100 equals just about three seconds in real world time. Three seconds to grab the pixie, put it in and grab a plunger to play measure 83 (I’m assuming the composer wants the flutter-tongued D to be closed or else I wouldn’t need the plunger). That’s bad but with the winds blowing the right way I can pull it off. Now, in the next bar I have a little more than three beats (one second or less depending on the accel.) to drop the plunger, remove the pixie mute, pick up the straight mute and jam it in my bell. Now I know why I’m supposed to “groan!” at measure 85. This falls under the heading of “impossible” mute writing.

There’s more. Just a few bars later in the piece I see this:

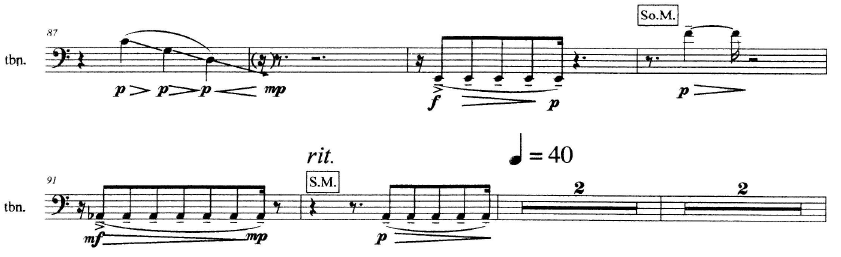

The first three bars are in straight mute, the passage is at qn=40. At that tempo I have about two seconds to remove the mute, put in the solo-tone mute for two bars of similar looking music, and another two seconds to switch back to the straight for more similar looking music. I don’t mean to question your vision, dear composer, but is the (not-so) drastic color change between the straight mute and the solo-tone absolutely necessary in this spot?

This second excerpt is what I would call borderline “improper” mute writing, but there’s no mistake, it’s “impossible” as well (two seconds is not enough time to do the switch). More clear cut examples of “improper” mute writing are: bucket mute in the upper register, wa-wa on a stemless harmon mute, practice mute at ff intended to be heard above a loud ensemble.

I’m sure I’ll discuss these issues with the composer and we’ll come to some workable solution but it would save us both some trouble if the problems weren’t there to begin with. In the meantime, I’ll continue to work on my quick mute changes and be on the lookout for the best way to travel with them. I’ll also be putting together a database of trombone mutes and their quirks. Be sure to check back for that.