Jason Price, a friend and trumpet player, recently forwarded a request from a friend of his. The person is working on a book on “inner monologue,” the silent thoughts running through your head during performance and is interested in hearing what goes through the mind of a musician during performance. This person (who is involved with theater) remarks that in the acting world “an actor should be thinking the thoughts of the character when performing.” He then goes on to qualify the statement by adding, “it is also nearly impossible to do so at all times as actors are distracted by personal inner monologue about the audience or other off-stage issues.”

This got me thinking about my own relationship with my inner voice. I feel I play my best when I stay out of my own way. When that “inner monologue” doesn’t show up.

“Whenever you think or you believe or you know, you’re a lot of other people: but the moment you feel, you’re nobody-but-yourself.”

e.e. cummings

The Internal Recording

The musician’s goal and challenges are essentially the same as the actor’s. I practice, and teach, that the aural imagination is at the forefront while performing. I’m playing at my best when I am simply following the recording in my mind. Playing along with the track that I’ve created in my mind by studying the piece on and off the instrument. When everything aligns and goes smoothly the sense of self is lost, there is only music. At its absolute best, the track is vivid and it’s not just sound. It is memories, it is imagery, it is emotion. There’s an entire movie playing in my head. It’s in slow motion, I have all the time in the world to make even the fastest of passages happen, but it’s over before I realize it. It’s kind of like the slow-motion passages from The Last Samurai (or the fight sequences from Sherlock Holmes):

[embedplusvideo height=”356″ width=”584″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/sEQlj54QlYo?fs=1&start=69″ vars=”ytid=sEQlj54QlYo&width=584&height=356&start=69&stop=125&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=&notes=” id=”ep1218″ /]

Hokey, yeah, but apt. I’ve heard it referred to as “superpilot.” As opposed to “autopilot.” Autopilot is like when you’re driving home, pull into your driveway and think, “how did I get here? I don’t remember that drive at all.” You lost control along the way, a little scary. Superpilot is when you maintain consciousness of the experience but are guided by something seemingly external. You’re in “the zone.”

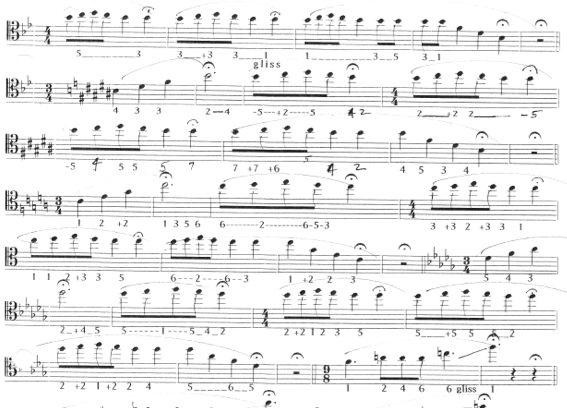

A little story: today I got a stack of music in the mail from Hickeys… if you don’t know the place, discover it, it’s a great music store. In the stack was Milhaud’s Concertino d’hiver. I’ve never looked at the music or played the piece in my life, but I did listen to Christian Lindberg’s recording of it countless times when I was in high school, nigh on twenty years ago. Playing through the piece tonight I could hear Christian’s performance clearly… it was like playing along with a recording. Not to say this was playing at its best. There were flaws and errors along the way. That internal recording is twenty years old and has holes in it. (PS. There’s good and bad to having this ancient internal track. The good being that I have a general sense of the piece right from the beginning of working on it… the bad being that I want to add my own personality to it and I’ll never have a blank slate from which to begin working. Larry Rachleff once said he avoids listening to recordings of pieces he’s working on until he’s sure of his interpretation.)

When Thought Steps In

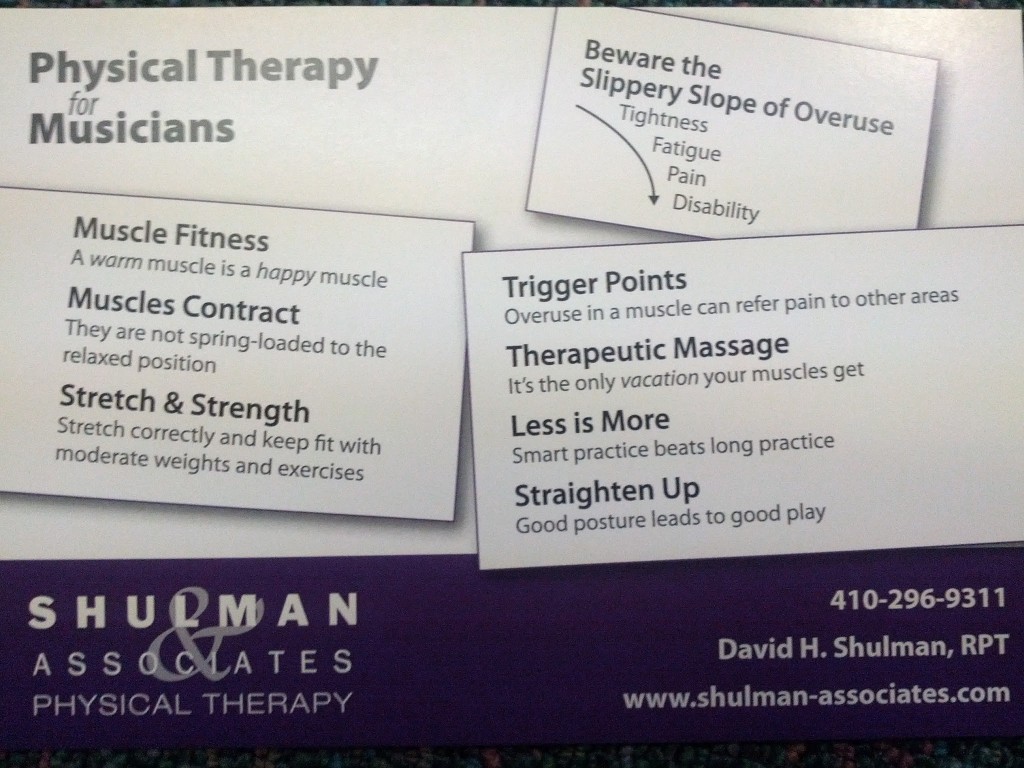

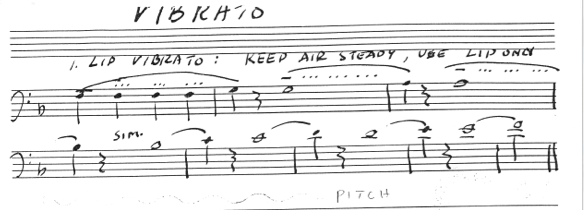

The holes are where the self enters. Consciousness, technique, effort. All the stuff we try to keep relegated to the practice room. Where to breathe, what notes to bring out, when to vibrato, etc. The questions are reserved for those times when you’re alone, creating that internal image. By the time you’re performing you want nothing but confidence.

Not every performance is ideal (in fact, I’d say the majority are not) but, like the limit approaching infinity, we push to come as close to it as possible, as often as possible. So what to do if the “inner monologue” steps in during performance? It will. It’s a fact of life. And dealing with it depends on what’s going wrong. Did I miss a note? Not a big deal. I’ve (hopefully) practiced the piece so many times that my internal CD won’t skip just because of a missed note. I’ll keep going in time as if nothing happened. More than likely my inner voice won’t peep. But what if it’s a bigger deal? What if I somehow miss a line of music or I’m playing in a group and someone else does? This calls for serious internal talk. Practical decisions must be made, and fast. Do I jump within the music to find the other person or do I make them catch me?

I recently had an experience like this with a “throw together” brass ensemble and a Christmas church performance. A trumpet player entered a measure early and refused to move to meet the other four players. Refused, or didn’t realize he was out of place. It took the conductor (the performance was with choir) calling out a rehearsal number to get the group back together.

The Breath

Once the music is back on track the goal becomes to live in the present, to “be in the moment.” No thoughts of what just happened, no thoughts of what’s to come, only what is. Breathing is the time honored locus of focus. Paying attention to the breath draws thoughts inward, away from the hiccup in the performance, to how you feel here and now.

Incidentally, focusing on breathing helps with performance anxiety (another thing that can obscure the internal recording). Many times anxiety arrises because of thoughts regarding the audience: “will they like the performance?” This brings up something called the Performer’s Paradox. We’re on stage because an audience is there to hear us, right? Actually the audience should be the last thing on our mind. We need to be true to ourselves and communicate what we believe the piece means without regard to what we imagine the audience will think… but we’re there because of the audience. Thus the paradox.

Imagery

Focusing on the message is the next step after the breath is restored (hopefully all this happens in the blink of an eye). What does the piece mean? What’s the message? It could be imagery. Playing Sibelius one might imagine a wind-swept heath and be transported to the right mental plane to perform effectively. Playing the opening to the Ligeti Chamber Concerto thoughts may turn to a primordial chaos, churning and morphing. The more vivid the image is seen, believed, felt, the more evocative the performance will be.

Creating effective imagery is a part of the rehearsal process, individually or in an ensemble. While I’m studying a piece I take time to develop a scene, a story, a deep emotional connection to the work. I’m more or less successful depending on many factors: how much I like the piece being a major one. The more I live with a piece, the deeper my connection to it becomes and hopefully the more affective the performance.

The Foundation

This is all assuming that the groundwork is in place. That the appropriate amount of work has been done in preparing the piece. Is the mental recording in tune? Are all the parts in time/in style? Has an appropriate sound been imagined to fit the work? Executing the fundamentals accurately goes a long way to create a successful performance.

And here’s the rub: maybe the successful performance, the one that raises goosebumps on audience and performer, is just an epiphenomenon of a fundamentally sound performance. Maybe all that imagery, all that emotion, exists only because the performer(s) has(have) heard in their mind(s) and executed the right wavelengths at the right time with the right sound. Or maybe it’s because they really felt it as they did.