The Trombone Glissando

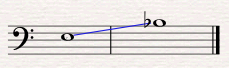

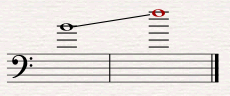

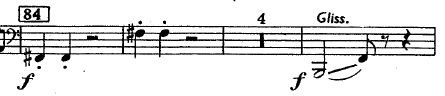

The single most common “mistake” I see in trombone parts is the unplayable glissando. Perhaps the most famous is from the fourth movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra:

Can’t do it (for reasons I’ll explain in a bit) but ugly little things like this keep turning up in my parts, maybe because one popular orchestration book calls it “perfect.” (Cough, Adler, cough.)

To his credit, Bartók probably knew what he was doing when he mocked Shostakovich. More than likely he was writing for someone playing a bass trombone pitched in F which would make this lick most playable. But 99.9999% of trombones today are pitched in B flat bringing us to the question of “what makes a trombone glissando possible?”

tl;dr: scroll down to the “Exhaustive List” below.

The Harmonic Series (You Should Know This)

To know what gliss a trombone can do you have to first understand the harmonic series, then understand the layout of the trombone. If you don’t know anything about the harmonic series take a second to digest that info (particularly the section “Frequencies, Wavelengths…”) I’ll wait here.

K, welcome back. Octave, fifth, fourth, major third, minor third, flat minor third, etc. You’re a better person now.

The Trombone (It’s An Extendable Tube)

Now let’s talk trombones. You’ll generally be dealing with one of two types: tenor trombones and bass trombones. There are plenty others: alto trombones, soprano trombones, contrabass trombones, piccolo trombones. They all work in the same basic way. Know what key they are pitched in and you are well on your way to figuring out how they tick.

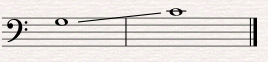

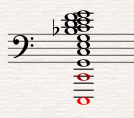

As I mentioned, the vast majority of tenor and bass trombones are in B flat. This means if you blow through the instrument with the slide all the way in you will get a note from the B flat harmonic series. Most professional tenor trombonists can reliably produce notes from the fundamental (B flat below the bass clef) to the twelfth harmonic (F at the top of the treble clef). Professional bass trombonists should be able to play at least up to the D below that F:

You can extend the slide (longer tube = lower sound) for six half steps giving you each down to the E harmonic series starting on the E two octaves below the bass clef:

For a bass trombonist the low E should be no problem. Depending on your tenor trombonist, that low E might be doable/might not. For tenors you should be safe down to the A flat:

Lower than that, ask your player. The more astute reader may notice that there are some notes missing, a fat diminished fourth from B natural below the bass clef to the E flat just above it. Trombonists have devised systems for playing these notes that open up opportunities for even more glissandi.

Valve Systems: More Options…

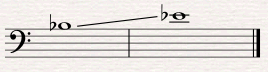

To make the trombone fully chromatic (or close to it) from its lowest to highest register, trombonists usually have a valve and extra tubing on their instrument. When the player presses a trigger and opens the valve the tube lengthens making the pitch lower. Professional tenor trombonists usually have a valve that will lower the pitch of the instrument by a fourth pitching them in F (giving them the F harmonic series when the slide is all the way in):

Remember, that low F may not be playable by your tenor trombonist.

More Confusion…

Here’s where things can get confusing. As you move the slide out with the valve depressed each subsequent half step is slightly further apart. In the end, the F valve (also called an “attachment”) can only lower you a fourth to the C harmonic series:

You guessed it, that lowest C will probably not be playable by your tenor trombonist. Now tenor trombonists are only missing one note: the B below the bass clef. For special occasions they can pull the tuning slide out on the valve section and lower the pitch of the valve to E giving them the E harmonic series down chromatically to the B harmonic series. You need to decide whether your occasion is special enough to ask a trombonist to do this.

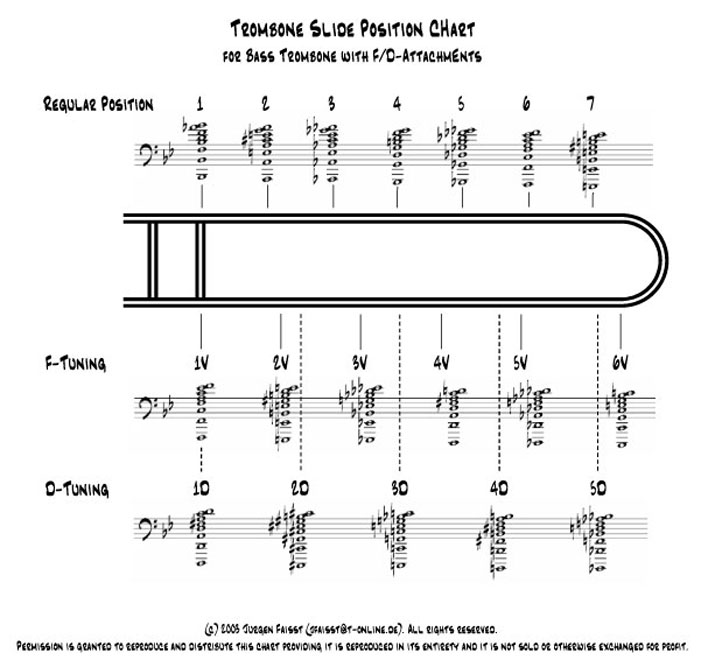

Bass trombonists generally have two valves available to them and here’s where things get really wild. There’s no real standard for what keys their valves are pitched in. Generally, they all have an F valve and some other valve that will give them that low B. One common system is one valve in F, the other in D (or the combination of the first and second will give D).

See below for a slide position chart by Dr. Jurgen Faisst that shows approximate positions and harmonics for the B flat trombone, the trombone with the F valve depressed and the trombone with a D valve engaged (notice that with the D valve the trombonist can only get a major third):

Possible Glissandi (The Exhaustive List)

Using the info above we can construct layer upon layer of glissandi.

B flat trombone glissandi:

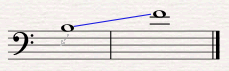

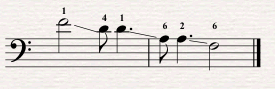

With the open B flat trombone these glisses can be as wide as a tritone. The first conceivable gliss would be from pedal E to pedal B flat but because of its extreme low register it’s not playable by all tenor trombonists:

The remainder of these glisses should be fine:

F valve:

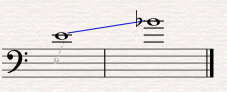

With the F valve depressed you get these glissandi (maximum of a perfect fourth):

The next two glisses overlap with those possible on the open B flat horn. The next unique glissando would be:

Any glissando higher than these can be produced without the F valve.

D valve:

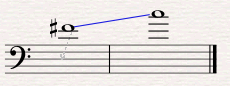

With the D valve engaged you get:

And…

Any glissando higher than that is playable either with the F attachment or on the open B flat trombone. You can use any of those in full or in part and have a playable glissando on the trombone.

Extending the Glissando

This is why the glissando from the bass trombone part to Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra is not possible on most modern trombones. (Most, but not all. There are some valve combinations that can handle it.) To get from that B to that F you have to cross between two harmonics. When you cross harmonics you get a “bump,” an audible break in the sound (think switching from normal voice to falsetto). Much like a vocalist can work to minimize the noticeability of his break, a trombonist can do the same. With the ability to hide that change and some quick slide motion larger glissandi can be achieved. Take for instance:

Or, better yet, if you’re working with more than one trombone you can begin another player on the pitch on which the first player ends:

Glissando Examples

In use the glissando can sound anywhere along the range of hokey to eerie. The hokiest probably being Lassus Trombone, the bane of every trombonist’s existence:

And the eeriest may be from the last movement of Ligeti’s Chamber Concerto. The trombone rises from the unbearably long oboe tone. (Side note: this movement covers basically the entire range of the trombone from pedal F to F at the top of the treble clef.)

Michael Daugherty uses the trombone glissando beautifully in the last movement of his Motorcity Triptych. First in a bluesy bass trombone solo then in a ethereal plunger mute passage with the trombone section.

Michaela Eremiasova uses the gliss to create an undulating texture and to add tension.

747 by Jim Pugh and David Taylor begins with parallel glissandi between a tenor and bass trombone.

The fourth impromptu from Jan Koetsier’s Five Impromptus (for trombone quartet) contains a glissando passed between the members of the ensemble to create a continuous gliss. (The continuous gliss starts around 0:33.)

Harmonic Glissando

A similar technique is the harmonic glissando. This is where the player quickly moves through the harmonic series. I’ll cover this in a future post.

Ask A Trombonist

Finally, when you’re done writing your part send it to a trombonist and have them check it out. They should be able to tell you relatively quickly if what you’ve done works. Look, here’s the email address of a trombonist right here: michaelclayville (at) gmail (dot) com.

13 replies on “Everything You Never Cared To Know About the Trombone Glissando”

If I may, I’d like to add a couple of notes to your excellent guide to glissandos, from a fellow-trombonist and composer:

Many wide interval glissandos are really unnecessary for the desired effect. I often get the feeling that some writers figure out a good tritone to use and immediately go for that (which is quite often unintentionally comical). But a small interval, even (especially!) a half-step glissando is very audible and just as effective. Perhaps Mike can comment to this, but as a matter of habit, I tend to add a slight crescendo to any gliss I play just to make it stand out (unless there are specific instructions not to do so).

Having said that, a “broken” gliss can be as effective a a “pure” one. I wrote a piece with a light-hearted ending where the trombones glissed from D in the middle of the bass clef staff down to G. Impossible to do “for real” under any circumstances, but: with only the written indication of “Broken Gliss”, they all played it perfectly the first time with no explanation. They glissed from D down to about C and slurred from there to G in one smooth motion. The sonic effect (this was an orchestral situation) was of a smooth gliss. This can also be done going upwards… gliss up from G to about A or Bb and slur to D.

Finally, I concur with Adler that compositionally, the Bartok gliss is if not “perfect”, then at least very effective (and it was indeed written for a triggerless F bass bone, the only kind in use in pre-war eastern Europe). However, by now that kind of thing is very clichéd. There are so many great glissando effects that most composers are not using, particularly in the opposite direction – very slow glisses, microtonal and the like. David First is doing some really great things (at least, in the little bits that I’ve heard).

I sometimes find myself doing what you mention (crescendo into a gliss), Russell, depending on the style and what I believe the composer had in mind. I tried my best to not make any judgement calls on which glisses work and which don’t (with the exception of my “hokey” comment regarding Lassus).

Regarding the broken gliss: I think the ability to play a passable “fake” glissando is an excellent skill to develop. Trombonists, in general, are pretty good at pulling off something that will work in most instances. But for those times when nothing but a completely microtonal glissando will do it’s important to know what is possible. 🙂

I’m not familiar with David First (though I’m checking out his music and website right now). Anything in particular I should be listening to?

What I know about David First comes from Kyle Gann’s blog:

http://www.artsjournal.com/postclassic/2010/11/symphonic_slide.html

Thank you for this! I keep needing to remind me about how this works when I write for the trombone.

No problem at all. I’m glad it’s useful!

This is a fantastically helpful article. Thank you for writing it.

You’re most welcome! All the best.

Thank you so much for the article. It’s so helpful for composers.

You’re welcome!

I still haven’t figured out if I can gliss the notes I want, but: what a great article!

Thanks and… what gliss are you trying to do? I can let you know pretty quickly whether it’s possible.

Thanks oh so much! This helps students (me) prove to directors that some notes just aren’t possible with out the F attachment. (He still doesn’t believe me…) This article lead to my school buying a bass trombone and a tenor with the F attachment. You, are a god.

Great to hear about the bass trombone! Pretty sure I’m not a god but I’m glad to be of help. For what it’s worth, you can play those trigger notes as “false tones” (http://tromboneforum.org/index.php?topic=31726.0;wap2). It takes a lot of practice to make them sound good, and even then it can be difficult to get in and out of them quickly (making them basically unusable for fast passages), but it can be beneficial to practice bending pitches.