For as long as I can remember I’ve begun my day with exercises that touch upon the fundamentals of playing: a “laundry list” of techniques such as ear-training, breath control, tone quality, articulation, flexibility, etc. The idea being that by playing these exercises I ready myself for the musical challenges of the pieces I face later in the day.

Thing is, these are all techniques that can be practiced or “improved.” I can tongue more quickly, make longer phrases, play louder/softer, etc. One of my first teachers, Jim Erdman, used to say “Always happy; never content.” It instilled in me a lifelong goal of “getting better.” With this interest in improving my ability I could spend hours on one skill: focusing my articulation, playing long tones… My “warm-up” began to take up the majority of my playing day.

This wasn’t so big of an issue in college, after all, it was my sole responsibility to “get better.” I could hole-up in a practice room for hours on end and play those long tones. But things have changed. Responsibilities (playing, family and otherwise) increased, as did the need for a succinct warm-up.

It’s taken conscious effort to develop a routine and a system for executing it that address the fundamentals in a timely manner. Developing this program involved:

- Understanding of the purpose of the warm-up.

- An organized view of the skills it takes to play the trombone (the aforementioned “laundry list”).

- A five-minute hourglass.

- A notebook (or Evernote).

1. What is a Warm-Up?

A warm-up is a set of exercises that get you ready for the musical day. Individuals will incorporate different studies in their warm-up but they have basically the same goal in mind. My goal is to be playing efficiently and comfortably by the end of my routine.

Players will feel “warmed-up” after different amounts of playing. Some warm-ups are a few notes (John Marcellus is fond of saying that he “warmed up thirty years ago”), some (including mine) are fifteen minutes to a half-hour and I’ve heard some players proclaim they don’t feel warmed up until they’ve played for three hours!

Generally, warm-ups are structured to gradually increase in intensity and cover all the techniques needed to play.

2. The Laundry List – Everything it takes to play the trombone

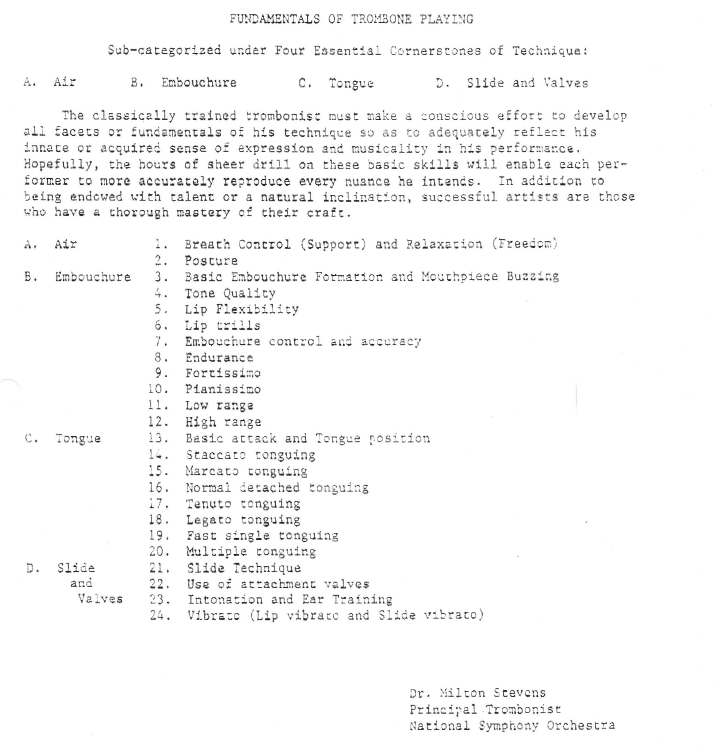

Milt Stevens, former principal trombone from the National Symphony recommended that you “make a list of every possible technique it takes to play your instrument.” He then went and did it pretty comprehensively:

I received this list during a masterclass with Milt in 1997 and I haven’t been able to find anything better. It’s what I use to be sure I’ve touched on every skill.

3. The Hourglass

So how does one be thorough but not take up their entire day on fundamentals?

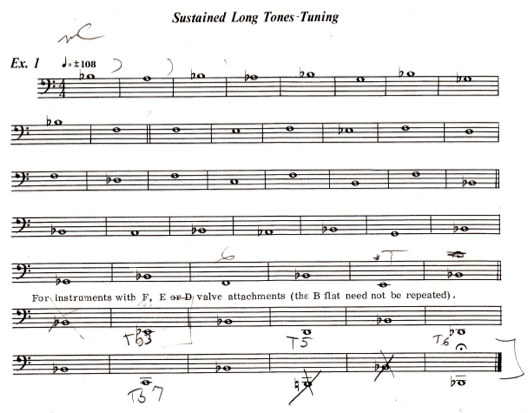

Some of the techniques can be addressed in a single exercise (posture can be combined with them all). Breath control and relaxation, for example, are pretty general and should always be kept in mind but can be addressed specifically in a long tone exercise that also addresses basic embouchure formation, tone quality, basic attack, slide accuracy and intonation. I prefer the Remington Long Tone Exercise:

That’s seven items from the list in one exercise, fourteen more to go. (You could even add vibrato into this exercise to cover that technique as well.)

By intelligently doubling (or tripling…) up on techniques the entire list can be dealt with pretty speedily. Keep in mind, if there’s a technique with which I’m having issues I focus on it with its own individual exercise. For instance if I had problems with multiple tonguing I would work on it in with its own exercise that eliminates (as much as possible) other techniques, for example: multiple tonguing on a single note.

The next step to efficiently making it through the warm-up is to regulate your time. Here’s where the hourglass comes into play. Instead of playing an exercise until it is “right” or it “feels good,” flip the hourglass (I find a five-minute glass is a good length) and play until the sand runs out. Once time is up go on to the next exercise. No questions. No backtracking. Guess what? You have tomorrow to do it again, and the day after, and the day after that. Five minutes is plenty of time to cover a technique, if you insist on getting more work on it after your warm-up you can choose some etudes that cover it as well.

4. Keep Records

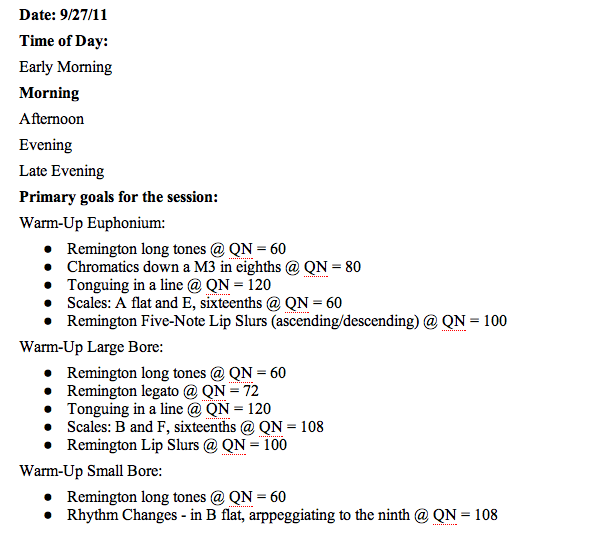

And finally. Document. Everything. Keep notes of your warm-up (and all of your practice sessions). Write down exercises, tempi and how you felt about all of it. What are your goals for the session? Were sixteenth notes at quarter note equals 108 too fast for you to articulate? Did lip slurs into the pedal range feel great?

Refer back to your notes. If you’re working to improve the speed of your articulation: know what tempo you feel comfortable, then bump the metronome up a few clicks. Play at that speed and take notes. When you feel comfortable at that tempo, bump it up again.

You’ll be able to look at your notes and see what you were up to when you were playing your best/your worst. Five years down the road you’ll have something to look back at and compare against. In conjunction with recordings this an extremely valuable asset.