This is intended as a resource for anyone considering writing music that utilizes trombone mutes. In future posts I will go through each type of trombone mute individually and talk about its quirks and uses, here I will explore the many things that are true of all of them:

1. “Mute” is a misnomer.

Despite their name, mutes don’t actually mute. In fact, many times, a muted brass instrument will sound louder than an open (unmuted) one. Mutes are filters: they amplify, pass or attenuate (emphasize, do nothing to, or de-emphasize) certain frequencies. A mute that removes the low frequencies and emphasizes the high can seem to project more than an open horn.

That said, some mutes will make the instrument decidedly softer: it’s impossible to play very loudly with a practice mute and, while penetrating, solo-tone mutes are not very loud. In the end it takes knowledge of each mute to know which will suit your needs.

2. Budget plenty of time for them…

I’ve seen my fair share of impossible mute changes. They probably tie with impossible glissandi as the most frequent “mistake” I see in parts. Know this… the time you left me to put in (or take out a mute) is probably not enough, just saying. If you want to test it out, just pretend: hold your imaginary trombone in your hands, reach to your imaginary mute with one hand while supporting the trombone with the other, pick up your mute and insert it into your trombone, give it a good twist, take a breath and play (it takes just about as much time to remove it). Depending on the mute this can take even more time: harmon mutes, for instance, have a nasty habit of falling out; be kind and leave even more time so the trombonist can wedge that thing in the bell and not ruin your piece with a heavy hunk of metal falling to the floor.

There are certain techniques that can save a precious second or so. If you’re really curious about these maneuvers you can check out my post for trombonists regarding mutes to see what they are. However, your best bet is always to simply allow ample time for putting in and removing mutes.

3. …at the right time.

Which brings me to when your mute change happens. As hard as we try we to put mutes in silently it’s not always possible, especially when rushed to do it. If possible, avoid quiet moments for mute changes.

Additionally, the visual element of the mute change can be distracting. Seeing a player fumble with a mute (again, this can be especially awkward for quick changes) during a particularly soft or solemn moment can really destroy a mood.

4. Mutes change pitch… add even more time.

When a mute is put into a trombone the length of tubing is changed and consequently the pitch is changed. Usually it gets sharper (shorter pipe – higher sound) but occasionally it will actually go flat. Some of these pitch shifts can be quite drastic. I’ll discuss details when I go in depth on each mute but know that if you want your mute change done right (ie. the trombonist to adjust his/her tuning slide) you need to leave even more time… and yes, that also means more time to put the tuning slide back after the mute is removed.

5. They are a pain to carry (especially on long trips).

Trombone mutes can be rather large and take up a lot of space in luggage making them difficult to carry around. Carrying one, two, or three is absolutely no problem but asking the trombonist to carry a larger mute bag than his/her suitcase may be asking too much. For local gigs a large number of mutes may just be an annoyance but for distant gigs the arsenal becomes another checked bag to pay for and to lug around in the foreign land.

Personally I’m usually happy just to have opportunities to perform and understand it’s a professional responsibility to travel with the tools of my trade but I humbly ask you, the composer, to try to realize your vision with fewer than seven mutes.

6. Terminology and notation.

We can thank 19th and early 20th century symphonic repertoire (music that involved one mute that would be used for a few notes) for much of the mute terminology. Now that parts require multiple mutes and switch between them freely a simple con sord and senza sord may not be sufficient.

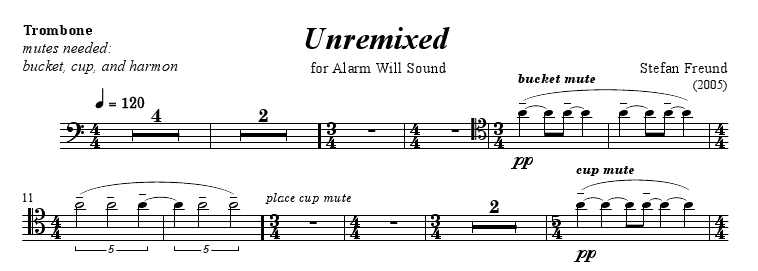

A list at the beginning of the part with the required mutes is exceedingly helpful. A quick look at the part lets me double check, when packing, that I have everything I need for the performance.

Instead of con sord use the name of the mute; senza sord or mute out work to notate the mute removal (which you should always do).

I’ll discuss open and closed symbols (+/o) when I do individual posts on the mutes that utilize them.

One reply on “Trombone Mutes: The Basics (For Composers)”

One of my pet peeves is when the composer/orchestrator/copyist doesn’t indicate which mute you need until the passage you’re supposed to be using the mute on comes around. Picture your example for “Unremixed,” but without the notation for “Place cup mute.” Maybe not such a bad thing with a piece you have time to prepare, but for sightreading, a disaster waiting to happen.