On the 21st, I went with Wes Thompson, a student of mine at Messiah College, to Shulman & Associates Physical Therapy. He’s been having some soreness in his face, most likely brought on by overuse, and he’s gone to Dr. David Shulman for treatment. It was an interesting experience. So often musicians have a “must do” attitude; they make it happen, no matter what the cost. It was great to see that there are people and a facility devoted to helping them rehabilitate when the (physical and mental) cost is too high.

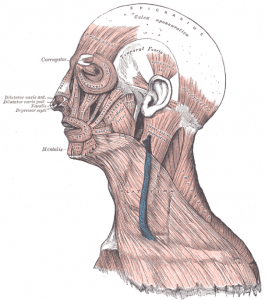

Wes began his appointment with a massage from Dr. Shulman. The doctor discussed the muscles of the face, specifically how brass musicians tend to focus their attention on the orbicularis oris and its ability to pull back the corners of the mouth while ignoring the fact that the muscle works in all directions. (I once heard Joe Alessi describe the muscles of the embouchure as a fireman’s net. The firemen pull in all directions to keep the net taught.)

The massage began with the large muscles around the cheeks and eventually moved to the lips. We talked about Denver Dill, a trumpet player who went through embouchure surgery and rehabilitation, and Lucinda Lewis, who has written the books Broken Embouchures and Embouchure Rehabilitation.

Doctor Shulman emphasized that players should be working toward strength, flexibility and endurance. His suggested path to getting there includes rest and practice away from the instrument. He recommends a routine that includes twenty minutes on the instrument and 10 minutes off, with 10 minutes of “nerf” playing (singing, humming) occasionally substituted into the twenty minutes of playing.

The therapy continued with the application of kinesio tape, an electric muscle stimulator and a heat pad.

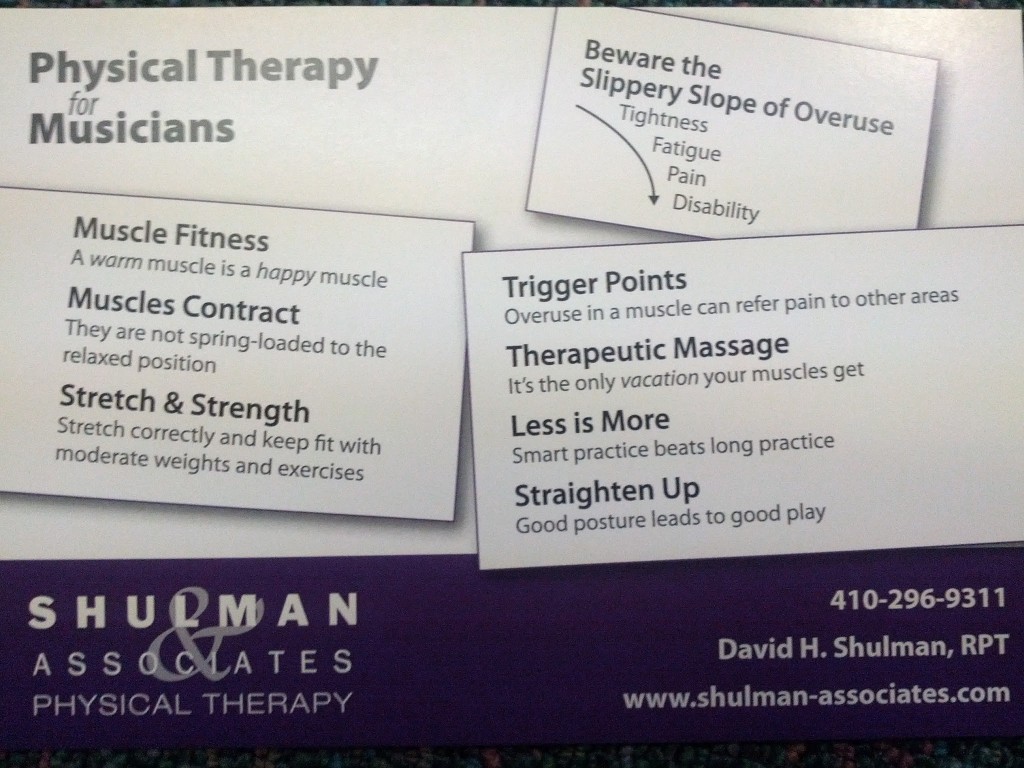

Shulman & Associates has a card that contains useful information. Particularly useful is the “Slippery Slope of Overuse:”

- Tightness

- Fatigue

- Pain

- Disability

Dr. Shulman’s practice has the added benefit of a partnership with David Fedderly, tuba player in the Baltimore Symphony and noted brass teacher. After finishing the session with Dr. Shulman, Wes headed to a private room to work with David Fedderly. David started with an old joke: “The National Institute of Health did a long drawn out study of musicians and rats and could only find one difference… there were things the rats wouldn’t do.” As musicians we’re taught to say “yes” regardless of whether we think we can handle all the work. Saying “yes” supposedly leads to more opportunities, experience and, sometimes, money. But saying “yes” to everything can also lead to overuse.

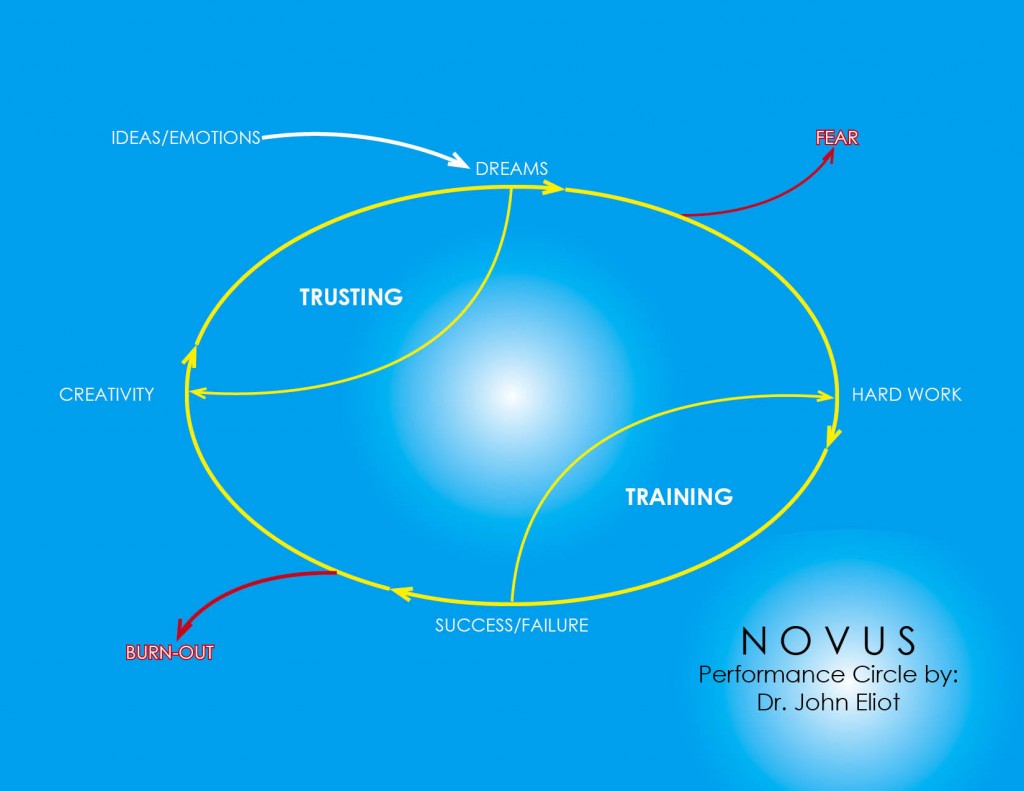

Once the overuse occurs, the player falls into the habit of playing in pain and needs to retrain to become accustomed to playing comfortably. David described an embouchure injury recovery like a back or leg rehabilitation: just because the muscle is healed doesn’t mean you can use it like you once did… yet. Getting well requires patience and small steps. Beyond that, once a physical recovery has been achieved it’s likely the mental recovery will take much more time. Fear and anxiety can, for some, build up while attempting to use the injured area. Attempts to use the muscle result in failure… failure becomes expected… the mindset becomes habitual.

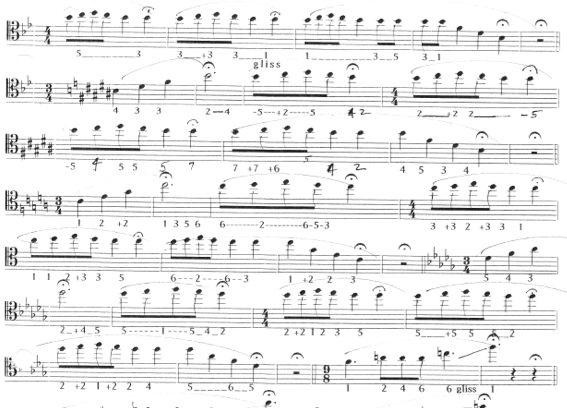

“Breaking a habit” is really creating a new habit and Mr. Fedderly emphasizes the habit of using sound and relaxation as your guide. He encourages the player to listen for the fundamental in the sound, in Wes’s case by asking him to allow himself to “play poorly.” By doing so he gets in the way of something we’ve all experienced… by trying to sound good we create more tension and actually sound worse.

I was glad to witness Dr. Shulman and David Fedderly in action. The duo is taking their act on the road: Dr. Shulman is spending the week at my alma mater, Rice University (which has a fantastic relationship with The Methodist Hospital Center for the Performing Arts), and both of them will be at the University of Oregon at some point this year. From what I understand they hope to share their knowledge with more performers across the country.